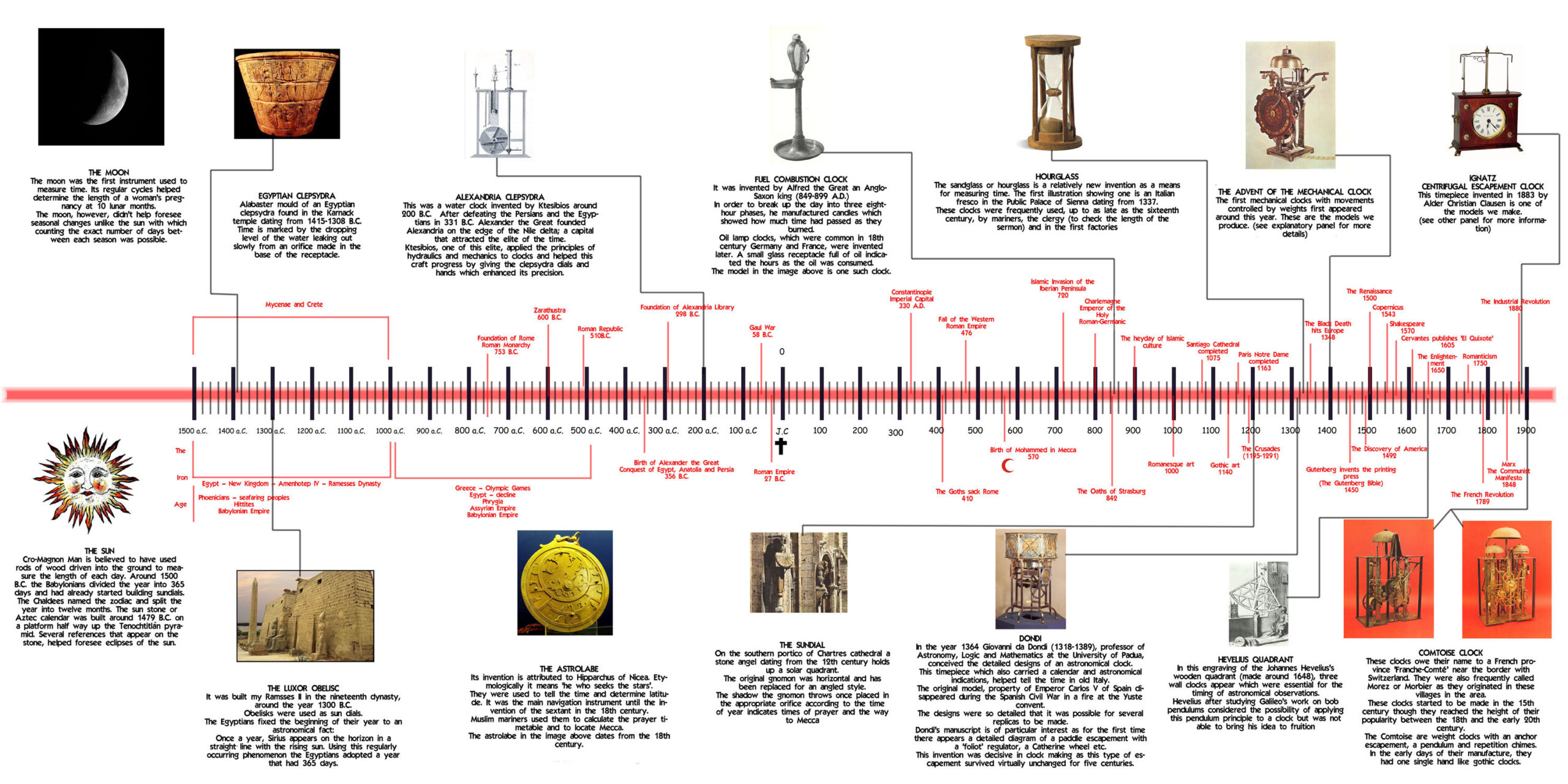

History and evolution of watches

It is interesting to know briefly the history of the devices and machines destined to mark the divisions of time until the advent of the mechanical clock on a nebulous date around 1300. To do this we will refer to the work of J. M. Echeverría, which is clear and concise.

The first clock of man was obviously the sundial whose history is lost in the dawn of civilization: the obelisks of the Egyptians, our menhirs and cromlechs were nothing but sundials and astronomical observatories

Sundials made up of a rod embedded in the bottom of a semi-spherical excavation seem to be Chaldean inventions and were already very popular in Greece, subsequently taking on multiple forms. Until the 18th century, sundials were still used because the sundial was still very useful for checking and setting the time of mechanical clocks.

Ancient clocks

Another type of sundial was the astrolabe, whose invention dates back to 150 B.C. by the Greek Hipparchos and whose subsequent evolution gave rise to the octant and already in the 18th century to the sextant that is still used in navigation today. But as honest and precise as our Father Sun is, it has its drawbacks: what if it is night, what if it gets cloudy? Medieval astronomers used a kind of astrolabe, called “nocturnal”, but in covered time the problem persisted.

Several gadgets were used with more or less fortune to solve this problem, although they measured short periods of time, such as hourglasses or fire clocks of very primitive origin which consist of measuring the time it takes for some combustible material such as oil or wax to be consumed. But the most widespread was the water clock or klepsydra of unknown origin, already present in Egypt. The principle is very simple: the water drips slowly from a first container filling a conveniently calibrated second, whose marks allowed the time to be checked. But this invention evolved until it reached its highest scientific expression in China, where the Buddhist monk L’HSING invented – in 725 AD – the first clepsydre with an “escape” like a water mill. The date is memorable, since the escapement is the fundamental piece of any hydraulic or mechanical clock, being in charge of regulating the movement, as we will see later.

Gothic clocks

Let us now focus on the mechanical Gothic clock, the first real clock, which is the protagonist of this exhibition. The mechanical clock is the machine par excellence, the pristine mechanism. From this rough set of wheels and iron bars that make up a Gothic clock derive not only our modern chronometers but also all our present and future mechanization. No one remembers anymore that from this primeval mechanism come the keys to the firearms, all the spring-loaded gadgets and all the devices that made automation possible. All the centres of “industrialisation” of the Renaissance developed from a still gothic charter: the manufacturer of mechanical clocks.

The regular and steady running of the clock is imposed by a regulator that represents the standard of time.This fundamental mechanism, consisting of the escapement and the regulator, deserves a detailed description: the escapement is the first known and despite subsequent highly refined inventions, it was to last in certain clocks until the middle of the 19th century. This escapement is composed of an axle or “verga” with two small paddles attached, forming a right angle between them.

This fundamental mechanism, consisting of the escapement and the regulator, deserves a detailed description: the escapement is the first known and despite subsequent highly refined inventions, it was to last in certain clocks until the middle of the 19th century. This escapement is made up of an axis with two small vanes attached to it, forming a right angle between them.

These paddles engage alternately in the teeth of a wheel called a “crown” or “meeting wheel” and popularly known as the “catalina wheel” in Spain, in memory of the instrument used for the torture of this Saint.The driving force makes the wheel turn, but the alternating movement of the paddles slows it down, and it turns in small jumps; it is this syncopated turning that produces the characteristic “ticking” of the clock and is the basis of all escapement systems.

But this alone does not guarantee the slow and regular running of the watch, it must be complemented by a regulator or time controller. The most primitive systems consist of a simple balance wheel called a “rocker” or “foliot”, which is a slotted bar with adjustable weights at its ends. This system is rigidly attached to the end of the paddle wheel escapement and has the task of imposing a certain frequency on the clock.

Naturally, the hour hand of these clocks has a single hand; the minute hand will appear with the pendulum, in the 18th century.